Preface to Notes from the Flesh: An Experiment in Self-Help Fiction

(Self-Interview with Thomas Odeski)

In late 1977 Walker Percy gave what I believe was the first self-interview. It appeared in the December issue of Esquire magazine. I came upon it years later and thought isn’t this nice. We take selfies—those photos of ourselves. We contribute a moment-by-moment self-gush of thoughts, feelings, interests, tastes and happenings to our social media outlets. We self-publish. And now behold, the self-interview—the perfect complement to our current mix of self-projection strategies.

However, the self-interview, in case you haven’t noticed, never got off the ground. None of my friends, as far as I know, ever tried it. Other than Percy’s, I’ve yet to see a self-interview show up in the magazine pages. And what about our politicians? They give interviews ad nauseum. But can you name one politician who has interviewed him or herself?

So I thought, I can do this; I can interview myself. Why not? Perhaps I can inspire others and jump-start a new trend. Perhaps all it will take is for someone to step forward and show how it’s done. Wouldn’t you gladly welcome one more strategy for delivering the “me” package?

I conducted this self-interview in my living room in Dallas, Texas on the afternoon of April 1, 2018, a hopeful day, a day for welcoming new developments.

INTERVIEW BEGINS:

Thank you for allowing me to enter your home and take up your time—on a Sunday even.

It’s not a problem, really.

Let’s begin by discussing your present state, or condition. The book hits the shelves soon. Amazon will carry it. You’ve got the web site up. And that cover design—snappy and attention-grabbing, to say the least. This has taken a few years. And yet here you are. You seem relaxed, self-possessed, in control of your life.

Tell us, how do you feel?

You want to know how I feel?

Doesn’t everyone want to know?

Have you read the book?

Why, yes.

Or maybe you skimmed it late last night, cramming for this interview.

Well . . . ah . . . I did read it quickly.

I thought so. I’m not sure you would have started with that question if you noticed how I used it in the story.

But to answer your question, looks are deceiving. Don’t be fooled by this recent suntan and my easy cool demeanor.

Okay. So tell us: what is going on?

Right now, I’m a jumble of nerves.

Nervous? I never would have guessed. Why nervous, when everything is going your way?

So far, I don’t see anything going anywhere. Perhaps you are unaware, I have not sold any books yet; and I wonder, will it sell? Can the reading public tolerate my treatment, let alone any in-depth treatment, of the most distressful aspect of the human condition?

So nobody has read the book.

Only a few friends and relatives.

Do you have a launch strategy to help generate interest, to boost sales?

I’ve considered bringing it out in limited edition.

I see. Restrict the number of readers and drive everyone crazy trying to get their hands on it.

What do you think? Could a first-time, self-published author succeed with that strategy?

How about we shift gears and talk about the book?

Alright. Fire away.

To be frank, I find your story to be quite unusual. You composed a fictional account, out of material gathered from non-fiction sources. Have you invented a new genre?

Hardly. In the past, writers composed stories and plays to illustrate or dramatize ideas they garnered from philosophy, literature, history, and etcetera. In fact, at one time most artistic expression was considered a submissive act. It was commonly thought truth actually existed, and it was external and independent of one’s self. Therefore it seemed appropriate to appropriate—to gather from others and give new expressions to well-accepted commonly-understood truths. These days, most artists are concerned with self-expression, delivering a truth unique to one’s self, and residing within one’s self. But traditionally speaking, there is nothing unusual about relying on content derived from other sources, even non-fiction sources.

Now hold on. Yes, you employ outside sources, but your story relies quite a bit on truth that emerges from the self. This seems very much in line with contemporary artistic values.

Perhaps you have a point. Maybe it would be accurate to say I draw from both directions to create one story—truth that emerges from the self along with the observations of respected scholars and others who have commented on the human condition. Is that unusual? I don’t know.

Oh, maybe some would find it curious that I am explicit about my sources. You rarely see that in stories. In Notes from the Flesh I work a fair number of book titles into the story. I even use the wording of some titles to make a point.

And you don’t think this represents a new genre?

I don’t know if we should call this a genre, or a new genre, or an unusual genre. Who cares? I wrote a story—that’s it.

Is there anything else unusual about your story?

The split-screen plot—I doubt you have seen many of those.

I have to say, it takes all my mental energy to stay engaged with those double-plot sections. That back and forth business wears me out.

You are not the first to gripe about this. Of those few who read the story, some seem unaware that creative works can operate on multiple levels.

Count me as one of those. I think your plot structure is convoluted and downright odd.

Oh, come on. Multi-tiered creative works are not uncommon. Take popular music for example. Are you not aware of musical numbers that combine two, and even three melodies within the same song? How about Dave Brubeck’s, Blue Rondo a la Turk, or Gordon Lightfoot’s, Canadian Railroad Trilogy?

Yes, but listening to those works involves hearing just one melody at a time.

OK, let’s consider Broadway musicals. A number of them, like West Side Story and Les Misérables, include songs that have characters singing different words to the same tune, simultaneously. This puts a burden on the listener to exert mental effort, and concentrate.

And what about those cubist paintings? For instance, Picasso’s Guernica—multiple images within one painting, all imposed on our senses simultaneously. Not all creative endeavors will soothe and relax. In fact often, just the opposite—some artists prod their audience to think or feel deeply, or take action.

For cripes sake, is it too much to ask my readers to exert a little effort?

OOOOOH. Feeling touchy are we? I take it you are surprised by the reaction to your bi-plot approach. Do you have second thoughts? Do you now wish you had devised a more conventional story?

Absolutely not. I employ the double plot because it is the only way to tell the story that needs telling.

You are not worried this could discourage readers; that some might set the book aside and give up; or even worse, post a negative online review.

Nah. In this day and age? No way. At the office, many of us monitor more than one computer screen to keep up with our work. On big game days, kids set up two or three TVs and watch them all at once, while fiddling with their phones. The multitasking experience is thoroughly woven into our every-day lives.

It occurs to me—and tell me if I’m on track—this seems like puzzle making. You cobbled various sources and arranged the material into a complex story to make a penetrating statement on the human condition. You undertook a challenging mental exercise to say the least. Like a climber facing a formidable mountain—you came up with this brainy Mount Everest requiring all your cerebral capacity, and you tackled it. Therefore, if we boil it down, your story is really just an intellectual, right-brain puzzle-making exercise. Is that it?

Oh, not at all. Notes from the Flesh is personal. It originates in my own story; a story involving a number of people, my own experiences, and material from books I read to expand my understanding of those experiences.

Can you elaborate?

Sure. Almost forty years ago, Susan and I had finished our education at Texas A & M University, and moved to Dallas. We were looking for a church to attend and …

Hold it. You were looking for a church? When newcomers arrive in town, don’t they first look for a place to stay, and for a job?

OK, yes, we had already arranged for a place to stay and I had nailed down a couple of part-time jobs. We were expecting our first child. This was the summer of 1979.

So you looked for a church.

In those first months we visited a few churches but failed to find anything suitable. A friend, who lived outside of Dallas, recommended a small church meeting on the east side of town. He had performed a wedding there for a couple of his friends. Then, in a child birth preparation class, we met this couple, Rick and Susan. They spoke with enthusiasm about their church, the same church. Two witnesses now pointed us in the same direction. We decided we should check this out.

One Sunday in late summer we found ourselves driving through old East Dallas. The church, as we found out, met in a defunct firehouse. The membership, mostly young people like ourselves, dressed casually (in jeans even). We walked in and were welcomed with a cup of coffee which we took into the main room for the worship service. Guitars and tambourines were on tap for the music. Keep in mind, this was decades before jeans, guitars and coffee made their appearance at the conventional Dallas-area church. Up to this point, we found these other churches to be quite formal and stuffy. Not only did we lack the clothes for those highfalutin venues, but we had both grown up in California where casual equates with authentic. We found ourselves feeling right at home with this funky, non-conformist, old firehouse vibe.

What happened that first Sunday?

Two things stand out. One, we received an invitation to dinner; and two, an event proved to be a sign indicating a key feature of this little congregation.

Tell us about the dinner?

This woman named Zoe invited us to join her, her husband Mark and a few friends for dinner the next Friday night—homemade pizza on whole-wheat crust. We went and met Henry and Jeanette and some others. Nobody at these other churches welcomed us in this manner—on our first visit even. It made a deep impression on Susan and me. These people seemed very much like us; young parents with infants and toddlers, college educated and somewhat idealistic. And they were friendly. So, we returned the next Sunday and eventually committed ourselves to the church.

You mentioned something else on this first Sunday, a sign regarding this group.

It had to do with the leader of the group, and his message that Sunday morning. He announced he was leaving. This individual (I found out later.) had been most influential in starting this church just a few years prior.

Did he say why he was leaving?

I don’t recall.

You said this was a sign.

Yes. But only later did I see the significance. His leaving expressed a characteristic of the group. At this church, people would commit themselves—not to a program or mission so much, but to each other. I mean this was intense—I’m talking passionate commitment. Everyone spoke incessantly about community. I think the word was mentioned every time we met. But then, after their involvement for a short duration—maybe just a few years— members would jettison their commitment and exit the community.

That does not sound like a pattern leading to success.

Eventually the number of those leaving outstripped those who came and stayed.

How long did you stay?

We stayed about seven years.

Why did you leave?

At one point a big chunk of the membership walked out. A handful of us remained for a few months but could not keep up with the bills. There was nothing left to do but close the doors.

Ok, let’s go back. You said a large percentage of the membership left. Do you mind if I ask how this made you feel? I know from your story you have a certain regard for that question.

I need to clarify my use of that question in the story. First, the question is relevant to my background and I will answer it. On the other hand, that simple question packs a boat-load of meaning regarding the times in which we live. Have you read anything by Phillip Rieff?

Yes I have.

I wish we had time to dig into his ideas. In short, within the story I highlight that question, “How do you feel?” to illustrate how we’ve constricted our understanding of self-identity. Oh, and I also use it to poke fun at the news media. I think nowadays these kids attend journalism school and come out knowing that one question, and not much else. Besides, have you noticed reporters? How tactless they can be when asking their one question?

If the question is relevant to your background, why do you dodge it?

Ah, fair point. OK, my feelings when the group left—I felt devastated, as if something has been ripped out of me, as if I lost my family.

Your family? That seems like an odd response—extreme, don’t you think?

Yes, I agree. In a moment I’ll come back to this family stuff and expand on it.

All right, so this small congregation played a role in the book you’ve written?

Regarding the book, the group affected me in a couple ways. First, a number of us have remained friends, and we meet regularly. We read to each other the things we’ve written, and we encourage one another to keep at it.

Also, while involved with the church, my life took a turn; a turn that brought me to some understandings which would affect the writing of my story, Notes from the Flesh.

An event took place having impact on the content of your story?

Well, not exactly one event. In the last year or two, before closing the doors, a bunch of us, maybe twenty or so, coalesced around a separate project. With the permission of the leadership we began to meet regularly away from the church. We divided into three small groups, called “Growth Groups.” Two of our group, Stan and Steve were professional counselors; they led the project.

What was the project?

The project centered on finding a pathway to emotional healing.

What? The twenty of you were emotionally damaged?

I won’t say “damaged” when speaking of others. I might mischaracterize someone. But the term damaged certainly applied to me. Yes, I was an emotionally damaged person.

For the others, for all of us on the project, let’s just say we had issues, emotional issues.

Oh yeah, emotional issues. I’ve heard that one before.

I hear your skepticism. I know how this term “emotional issues” strikes some ears, conjuring associations with narcissistic and self-absorbed.

When I speak of issues I refer to patterns of unhelpful emotional responses affecting our behavior in relationships. Children, when responding to traumatic events, will learn to protect themselves with a set of behaviors that become habitual. But, these habits prove unhelpful when carried over into adulthood, and can hinder our function in relationships.

You sound like a textbook for psychology. How about you describe for us your emotional issues, or damage, or whatever it was.

When I was four years old, my father died, leaving my mother to fend for herself with two toddlers and an infant. She got herself a job to support us, but it wasn’t enough. Desperate—and within twenty months of my father’s passing—she accepted a marriage proposal from another man. This man was much older, imposed discipline on me and my brothers characteristic of his military background, and subjected us to his rages, verbal abuse and even physical abuse. And he was unstable; right after they married, he checked in for a five-month stay in the psyche ward at the VA hospital. I later found out he kept a gun in the house and threatened—to my mother—to commit suicide. Combine all the above with substance abuse—prescription tranquilizers and alcohol—do you see the picture? When I was thirteen years old the stepfather died. For the remainder of my youth I grew up fatherless.

You are telling me what happened. But how were you damaged?

I’ll describe three effects that carried over into my adult years: loneliness, an abiding sense of guilt related to an inappropriate burden of responsibility for the well-being of others, and numbness.

First, loneliness. The two deaths made me think I was unique; as if I was marked, or cursed in some way; as if I had been called out from the human race to form this special bond with death. Even as a child, and on into my teenage years I felt different from others. I had friends and normal teenage activities to occupy myself. But still, I felt lonely. Later, I developed this intense longing for my father. Though just a toddler when he died, I still retained these pleasant memories of our times together: wrestling on the floor after dinner, going places in the car, following him across the yard and carrying his tools. Occasionally, as an adult, I would dwell on these memories. When I did, I felt painfully lonely and craved his involvement in my adult life. I especially wished he could have known Susan and our children; and seen the work I do.

In addition, my father’s death affected my understanding of myself. Not long afterward—I was only four year’s old, keep in mind—someone, either a grandfather or a friend of the family, said something that made a deep impression. I was the eldest son, and therefore my father’s passing meant I had become “the man of the family.” These words stuck. Later when my stepfather died I took on this burden of seeing myself as the caretaker. Of course, as a teenager I hadn’t the knowledge or resources to care for anyone. But still, I maintained this sense of responsibility, along with intense feelings of guilt when things did not go well with my mother or brothers.

Substance abuse compounded the effect. The term here is co-dependence. It refers to a syndrome affecting those who live with drug addicts and alcoholics. Overindulgence debilitates the parent and reduces their function: they slough off responsibilities, they are not as alert, and their emotional range oscillates from the maudlin, to anger, to superficial gaiety. Because of their reduced function, they become dependent on other family members, including their children who are forced into the role of caretaker.

My mother relied on me for two main responsibilities: the physical upkeep of our house; and providing a role model for my younger brothers. No, relied is not the term. As she admitted to me years later, she “leaned on me too hard.” Her desperate emotional tone when making requests of me and her late-night crying made me think my duty was to prop her up; without me—“the man of the family”—everything would fall apart.

So, this dysfunctional environment—her dependence on me, our economic vulnerability, the strangeness of those two deaths—pressed upon me a dark and heavy burden. I came to believe we were trapped within something I was supposed to fix, or alleviate. Within my emotional makeup, I felt like a failing parent, oppressed by an abiding sense of guilt.

So later, as an adult, you were still affected?

Oh yes. Fast forward twenty years. Now I’m married with my own children, but I am still responding to those around me as that guilt-laden teenager. On the outside, I appear to others as a responsible person, going to work each day, taking care of my family, on a trajectory toward a solid and successful life. But on the inside, at times I felt like a wreck—from the guilt and this oppressive burden of responsibility.

A moment ago you mentioned the church break-up and how it devastated you, as if you lost your family. Was this related?

Oh yes. Family dynamics follow you, and they followed me. I learned later it is common for adults to function within groups according to the dynamics of their family of origin. With our little church community, I was taking on new responsibilities . . .

Wait. You just told us you were plagued by guilt feelings and a heavy burden of responsibility. Why would you take on more?

The word is dysfunctional. This is what we do. We act against ourselves by making unconscious decisions to recreate our family of origin experiences; to compensate for our childhood losses. By taking on new responsibilities—by always saying “yes” to whatever was needed—I was making this group into my family. Therefore, when people left, I felt abandoned—my family left me.

That sounds sick.

It is sick. I was sick.

You also mentioned “numbness.”

My emotional life functioned like a dim flickering light bulb. I experienced guilt and loneliness as a vague tenseness in my stomach; I thought of it as feeling bad. But I lacked precise understanding of what was happening, and I had no vocabulary for giving expression to my experience. In addition, there is a spectrum of emotions I did not, or could not feel. This ignorance of my emotional function originated with my father’s death. When he died, I did not feel.

What do you mean? How can someone not feel?

This is one those protective measures children will adopt. How could I, as a four-year old, absorb the tragedy and loss confronting me? On an emotional level, I could not handle that. Therefore, I protected myself with numbness, by shutting down my emotional function. Of course I did this unconsciously—I had no awareness of what I was doing.

Like an autonomic response?

Yes. Suppose you have intense pain in your arm when you move it a certain way. You will shield yourself from the pain by not using your arm; by eliminating the function. After a time you won’t even realize what you are doing. This is what I did with the loss and sadness. And, like that unused arm, atrophy can set in. The source of the pain may later dissipate; but from lack of use, the emotions don’t function in a normal manner.

My father’s death was followed by those eight years with the stepfather. He would not tolerate our childish outbursts, our loud and raucous playing. In his house, we had to “keep a lid on it,” which translated into keeping a lid on “me.” The rager functions like a totalitarian ruler taking for himself all the space for self-expression. He robs others from opportunities to say what they think or feel. And not only is self-expression snuffed out, but my mother, brothers and I wallowed in fear, dreading his next outburst.

It astounds me that so much can be going on behind the surface—to an individual, to a child even—and it goes unrecognized by others who stand right there in the same room.

You got that right. I repressed it all: the extreme loss and sadness from my father’s death; the daily terror of living in my stepfather’s house, and then the guilt and overwhelming burden of my teenage years. I was growing physically, but my habit of numbing myself, while allowing me to survive, also induced my emotional handicaps.

Coming into my adult years I saw myself as a rational person, who made sensible decisions. I was blind to how the emotional damage was giving shape to my life. In our Growth Group, I finally acquired the mental categories and the vocabulary for recognizing and expressing what was happening on the inside. I began taking steps to reverse the damage.

Let’s move this along. I want to put forward two assumptions and I want your feedback. This Growth Group played a role in helping you recover from these childhood effects. And, in your recovery, you learned things you incorporated in your story, Notes from the Flesh.

You are close. In my Growth Group I learned things that caused me to ask questions—two questions. One of these would draw me into thinking through the major ideas for Notes from the Flesh. The other question would lead me to write the book.

What are these two questions?

I first need to mention two books.

I’m aware that you wrote just one book. Are you saying you wrote another book?

No, dang it. I am speaking about books we read in the Growth Group.

Oh, sorry. But what about the two questions?

We’ll come back to the questions. But first the two books.

Ah, books. I get the impression you like books, that you use them as tools for navigating life. And, you had much to say in your story about the word more. Would it be fair to conclude that your attachment to books constitutes your form of Morism?

Oh yes, Morism. I admit, with me there is always one more book.

You mentioned two books.

Most of us in the Growth Groups were college educated. So, as to be expected we began our new endeavor by gathering more information. The first book we came across was Soul Making by Alan Jones.

Sounds like an odd title.

Soul Making is about the formation of persons—how the self, or in Jones’ terminology, the soul is formed. The making of a soul, according to Jones, involves learning how to receive and return love; a life-long process. He uses this expression, “the school of love;” he says we are all enrolled in an ongoing “school of love.”

It seems these days everyone wants to talk about love.

Tell me about it. Walker Percy said love is the most polluted word in the English language. Hey, that reminds me. It was because of Jones’ citations of Percy some of us got familiar with him and read his works.

I noticed Walker Percy figures in your story. You mentioned him by name, more than once.

Yeah, that’s right. In those days we were reading his novels. But later I came across his non-fiction works. These affected my outlook and found expression in Notes from the Flesh.

I want to get back to Jones. Are you saying Jones’ ideas on love affected what you wrote in Notes from the Flesh?

No, not really. But Jones’s book had a serious impact on me, in a couple ways.

Oh. So now we have two impacts.

From Jones, yes.

I came into this Growth Group experience with doubts about this area of emotional healing. I understood the purpose of psychological counseling and could accept it as necessary for some people. But I also had misgivings. Some within our faith community thought a secular profession like psychological counseling would cause you to lose your faith if you got too deeply involved.

I learned from Jones it was possible to commit oneself in both directions; one can pursue emotional healing and pursue one’s faith, and they can complement each other. According to Jones the purpose of our Christian faith is to help us become better lovers of God and others, and the purpose of emotional healing is to help us shed those hindrances blocking us from receiving and giving love.

This was the first impact from Jones on my Growth Group involvement. He helped me get over my fear of the psychological profession.

The second impact related to things he wrote regarding self-identity. Once I got involved in the Growth Group I soon learned emotional healing involves narrowing our understanding of self.

Narrowing?

Yes. Let’s go back to my example of the malfunctioning arm. Suppose that pain in your arm was caused by an injury, and now you require surgery. You check into the hospital, undergo your surgery, and then recover for a day or two. Afterward you follow up with a few months of physical therapy. For a time, your life is all about the arm; about getting it healed and restoring it to normal function.

Emotional healing can follow the same trajectory, at least it did for me. For a time, I needed to focus on this intently. But when I say intently, I mean more than just attending group meetings, reading new books, practicing a new vocabulary or making daily entries in my journal. I also needed to understand myself in a particular way, for a time.

You’re losing me. My readers and I need specifics.

This was either stated in one of our meetings or I read it in one of the materials. We were told that the “I,” the me, the person who I am is defined by three things: what I need, what I feel and what I want.

So, you adopted this view of the self.

Yes, I had to. For the sake of emotional healing I entered this period where I understood myself exclusively in terms of my needs, my feelings and my wants.

How did Jones factor into this?

Jones widened my perspective. He points out that, for a person of faith, the question of self-identity is both open-ended, and much larger and more wonderful than we can fully grasp now. My Christian faith specifies a future where the conflicts and tragedies of this world—including those related to myself—will be resolved. Therefore, the who-am-I? question must remain somewhat unanswered, for the time being. But it will be resolved.

I recall a section from your book where one of your characters speaks quite expansively on self-identity, as if there is a wide spectrum of meanings related to our humanness. Is that from Jones?

You refer to my bank-robbing linguist. Yes, Jones started me thinking along these lines.

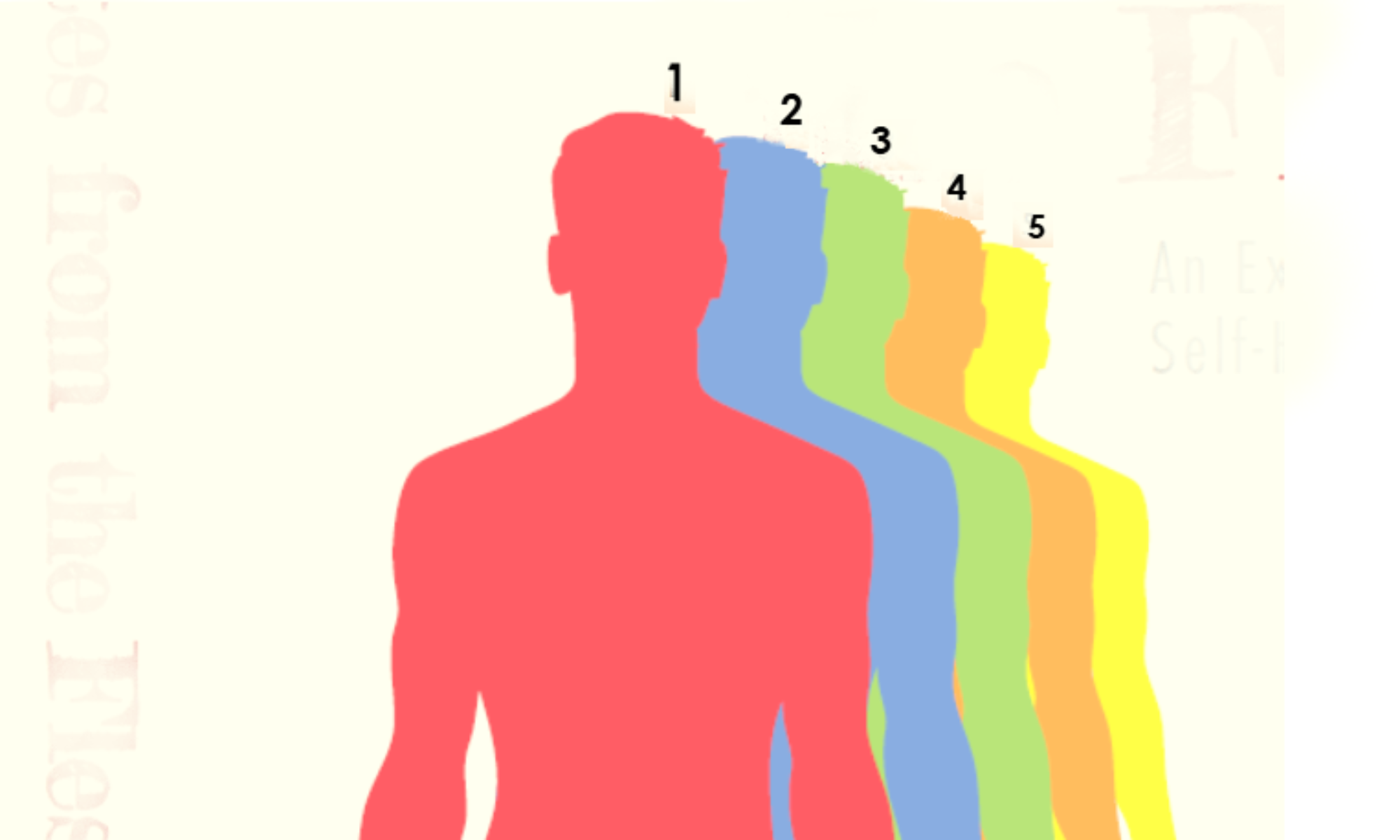

In Notes from the Flesh I attempted to show how our unconscious anticipation of death affects self-identity, here and now. I bring in the bank-robbing linguist to place the self-identity issue within a broader context. He speaks about the complexity, and even the mystery surrounding this question of who-am-I?

You also refer to Alasdair MacIntyre on this issue, do you not?

Yes. MacIntyre’s After Virtue, which I read years later, also proved instructive. He opens with a description of our two dominant modes for self-identity. On one hand, we are the emotive self, we think of self as our personal needs, feelings, wants and rights—very similar to what I learned earlier in the Growth Group. On the other hand, we have a bureaucratic self, the self required for the world of work—the one who adheres to regulations, procedures, the clock, efficiencies, professional standards, deadlines, sales goals, best practices, codes and scripts. MacIntyre highlights the glaring schizophrenic-like contradiction. These two types of self have nothing in common, and yet our age requires our conformity to both.

Let’s get back to Jones. I heard you say three things. This book Soul Making helped you become more open-minded regarding the process for emotional healing. And, for the sake of healing it was necessary for you to adopt a narrow understanding of self-identity—for a time. But even in the midst of the healing process, you knew the self—your self—was something broader and more mysterious than the self addressed by the healing process. Is that a fair summary?

Yes. Well done.

Let’s move this along. What about these two questions that affected your writing?

Not yet. Remember our group found two books instrumental for our project. I need to discuss the second book. It was Taming Your Gremlin by Richard Carson, a self-help book.

Gremlin? Wasn’t that a car from the nineteen seventies?

Yes, the term refers to an ugly creature. Carson uses it to describe the narrator inside many of our heads. The narrator talks to us and maintains a running commentary about our doings—often a negative commentary. Our narrator may be an overbearing judge, or a relentless hard-driving coach, or a frustrated princess, or a nagging mother. The comments can range over various topics, such as: how lazy or how stupid I am; or how I should do more for others; or why don’t I try harder; or nothing I do ever turns out right; or if only I could get out of bed earlier in the morning; or how much better my life would have been, if only… Some of us give the relentless voice great authority by associating it with God, or with our conscience, or with perverted notions regarding humility or self-discipline or whatnot.

From our non-stop listening, we maintain ourselves within a perpetual negative stupor; we find ourselves feeling bad in every situation—with our work, our relationships, how we look, our achievements or lack thereof—with everything.

“Feeling bad?” What do you mean here by feeling bad?

There are people, many of us in fact, who feel guilty, feel ashamed and condemned—perpetually. We live within a cloud of self-condemnation. This interior voice never allows us to feel at home with ourselves, to just feel at peace or comfortable with the persons that we are. And the narrator berates us with a million reasons why we should never feel comfortable.

Jesus says that a person speaks of the things filling their heart. If you listen closely to people you will hear a lot of self-condemnation and self-hatred, projected as criticism or judgment against others.

And this was you?

I experienced much of my life within the conditions I just described.

So in your head, you had this accuser berating you for not doing enough for the people in your life. And this interior dynamic kept you locked up in guilt feelings.

That’s an accurate way to put it; I was never doing enough. I saw myself as a perpetual disappointment to others.

I assume you tamed your gremlin. How did you do it?

Carson puts forth a three-step method. The first is observation—of yourself. He recommends we focus our attention on our bodies and become aware of how our bodies react in those uncomfortable emotional situations. In other words guilt, loneliness, shame, anger, fear—like all emotions—find expression in our flesh. You might notice that along with certain feelings your breathing becomes shallow, or you slump forward or sag your shoulders, your eyes narrow, maybe your stomach or throat tighten, your brow furrows. The first step is to pay attention to what is happening. He calls it “Simply Noticing.”

Sounds simple—just become aware.

Yes, it is simple. But for me, not so much. Remember what I said about numbness. I had made a habit of not experiencing emotion. I had feelings like everyone else. But they were tiny sparks of emotion. Even with guilt, my dominant emotion, at times I barely perceived it. Carson’s recommendation to “pay attention” to my body gave me a tool to help recover that dormant and atrophied side of myself.

At first I felt awkward doing this. According to my childhood and teenage years, and then later within the faith community, it was drilled into me: don’t think about yourself—that’s selfish.

Would that be gremlin speak?

Yes, that’s right. Very good.

So, you became comfortable with this new way of thinking about yourself.

I had to for the sake of recovery. And today, I continue to put this to use when I find myself reacting in relational situations according to my old patterns, with blankness, or numbness.

You learned to learn from your body.

Exactly!

Well there it is. One of your big themes in Notes from the Flesh. Our bodies can instruct us.

Precisely. If we pay attention, we can learn from our bodies. Later, upon reading After Virtue, by MacIntyre, I learned we should pay attention to our conflicts. So I joined the two—Carson and MacIntyre—we learn from our bodies we are in conflict; and conflict, as MacIntyre points out, has educational value. And then there is Earnest Becker and his work, The Denial of Death. From him I learned how our abiding fear of death—a repressed conflict—finds expression in our actions. Those three: Carson, MacIntyre and Becker gave me the main ideas for Notes from the Flesh.

Let’s go back to Carson. You mentioned there were three steps for taming your gremlin. You only told us the first.

For the rest of what Carson has to say, you’ll have to buy his book and read it for yourself. That first step of simply noticing proved most decisive in leading me to the question that generated the ideas for Notes from the Flesh.

Ah, so we are finally ready for the two questions?

The first, yes. After the Growth Groups, at some point, I asked, “What about death?”

And you asked that, why?

Because death was still my special concern. Carson taught me to pay attention to my body. Well, I remembered what happened when my stepfather died.

You had a strong physical reaction?

You better believe it. There was no numbness then. I recall vividly the wracking upheaval. Every morning, upon waking, this wave of pain and torment washed over me. My whole body ached. I felt that pain in my heart, as if a hole had opened. I remember my arms—they felt weak and hard to raise. This went on for days. At the time, I had no understanding of grief, and what it does to one’s body.

But why? You told us of his abusiveness. Why grieve over someone who abused you?

I cannot explain it. Later, others would tell me I was experiencing the unacknowledged grief from nine years earlier, when my father passed away. Perhaps. On the other hand, maybe my body reacted to a death that was proximate. My stepfather died from a heart attack in his bedroom, not ten feet from my room.

So you connected this memory of grief from your stepfather’s death—the physical upheaval—with Carson’s ideas on paying attention and learning from your body.

My question “What about death?’ morphed into “What can we learn if we pay attention to our bodies at those moments when we brush up against the reality of death?”

And that is how you developed your understanding of the Five Signs.

Yes.

What led you to write, to make a story of what you learned?

Now and then over the years, someone would encourage me to write down things that popped out of my mouth. My wife Susan mentioned this as did a couple of friends, Gary and Barbara. Years earlier, at the firehouse church, a woman name Cherry heard me teach. She approached me afterward and said I should write.

But also, there was something else. At some point, not too long after the groups ended, I began to ponder another question: “What about my inner adult?”

Your what?

My inner adult. Let me explain.

Back in the Growth Group we were assigned a book which dealt with how childhood traumas affect our inner child. Within some circles of the therapeutic profession, it is assumed we have a child self. This self represents the person who I really am—the authentic me. But my child was hurt and abused in those early years. Therefore, now as an adult I am crippled, unable to live out the authentic me and instead I live out a false me.

I’m not sure I understand.

If you observe children who are free from fear—maybe they are raised in a loving home by wise parents—you’ll notice particular characteristics. Children tend to be spontaneous, fun-loving, playful, inquisitive, willing to take risks, etc. They easily experience joy and laughter. Some children—many actually—speak and play quite loudly. Homes like mine, those inducing fear and guilt, suppress these childlike tendencies.

If I assume my suppressed, inner child represents the authentic me, then the goal of therapy is two-fold: first, gain awareness of, and appreciation for my lost inner child, and second, give that child permission to express himself in the world, here and now.

So what’s the problem?

I saw it as a two-fold problem, one related to anatomy, and one related to commitment and responsibilities. First, you know from reading my book, I believe anatomy teaches us about identity. If I exist as, and within the body of an adult, how can I achieve authenticity by living as a child? This inner child model for self-identity runs contrary to my adult body, to who I am. Secondly, I had responsibilities to my wife, my children and my employees. They needed me to function as an adult, not a child.

So, as an adult you find it more authentic to forget about your childhood, and this business of adopting a childlike approach to life?

Well no, not exactly. In order to benefit from therapy I understood the need to visit those childhood traumas and even experience through our group work what was lost, and my grief over what was lost.

Also, I well understand how I am handicapped as an adult because of my childhood losses and the emotional damage. And yes, I possess some childlike features within my personality. I enjoy giving playful expression to my sense of humor and I enjoy teasing others (I express both of these in Notes from the Flesh, by the way). And yes, when I get on the floor and play with children, something childlike comes alive within me, something that resonates with these playful experiences. But, I could not accept this idea that the primary expression of my authenticity would be child.

Have you seen the movie, Forrest Gump?

Yes. I liked it very much.

Yeah, me too. That film expresses a myth about children.

Forrest has a very low IQ. He illustrates traits from the Autism Spectrum and he expresses a childlike innocence throughout his years, even as an adult. He is honest, generous and kind. Forrest never acts out of pride, greed or ambition, qualities we might associate with adults. The story presents him as an authentic human being. But Forrest is also quite powerful. In college he becomes a football star and receives a full-ride scholarship. He performs heroic deeds in the Vietnam War. He becomes a wealthy philanthropist. In the end, he wins the girl of his dreams, a childhood sweetheart whose damaged life is partially salvaged by his love. He accomplishes all the things any of us would want—and he remains a child.

The film was popular. Tom Hanks gave a dynamite performance as Forrest. Like others, I enjoyed the nostalgic romp through the personalities, events and music of the sixties and seventies. But I think this movie goes over well for one additional reason. It keys into a myth: if we could be more childlike, we would get what we want in life, and we would cure the ills of the world at the same time. That’s what this child Forrest does—he gets what he wants and he fixes the world around him.

Why do you call this a myth?

Because, despite the valuable ways children enhance our lives, children will not change the world. A child’s body is incapable of reproduction; they do not give birth and nurse babies. Children do not teach in schools. Children do not work in hospitals and heal the sick. Children do not put out fires. Children do not take on construction projects and see them to completion. Like it or not, adults rule the world—for better, or for worse.

Where does the myth come from?

It derives from therapy, or at least from recovery-oriented therapies. Most of these pursue healing by helping clients understand, and then reverse, the damaging effects from childhood traumas, traumas imposed on us by the adults. This therapeutic bent then crosses over and nurtures this belief in children as authentic and adults as inauthentic.

Whoa there. You’re losing me. What do you mean “crosses over?”

The values, the thought patterns, the theories that populate the diagnostic profession of psychology cross over and become material for our social outlook.

Social outlook?

Check out Philip Rieff’s work, Triumph of the Therapeutic. He describes the process by which our culture has been shaped by, and gives expression to, non-rational myths (he calls them faiths) which have grown out of this profession of psychology and the healing of damaged persons.

So, you asked, “What about my inner adult?” And . . .?

I came to a couple of realizations. Have you seen the movie, Good Will Hunting?

Oh yes. I liked that one too.

Here we encounter a story demonstrating the power of emotional healing.

Matt Damon plays the emotionally damaged young man. He was orphaned as a child and suffered horrendous abuse in the foster home. He also possesses the brain of a mathematical genius, maybe on par with Einstein. But because of childhood trauma, he cannot function as an adult—he is paralyzed. He fails to move forward in his relationship with Minnie Driver; he ties himself to menial jobs ill-suited for his mental abilities; he closes each day hanging out with childhood buddies who pursue two ambitions: put in their eight hours swinging hammers, and drink beer all evening.

Robin Williams plays the therapist. He forces Matt to take an honest look at his background and confront his present-day failures and disappointments. Matt achieves a break-through. He then makes decisions to orient his life in a new direction. He accepts employment suitable to his mental strengths, and he takes steps to reverse that damaged relationship with Minnie Driver.

He found his inner adult.

Exactly.

And you did also?

In stages. First, finding my inner adult had to do with changing my posture in relation to my family—and also in relation to my business. As the result of my group work, I achieved a marked degree of freedom from the guilt and the overwhelming sense of burden I had inherited from my childhood. With the people in my life I was able to relax. I ceased the constant fretting about what I was, or was not doing for others. My relationships became less of a burden and more of a gift to be received, nurtured and appreciated. Also, I gained some know-how for recognizing and expressing the emotional side of my personality.

The wounds from the past sometimes exert their influence and I find myself slipping into old patterns. But the Growth Group gave me the tools to deal with this. I believe our group—the other members, the leaders, what I learned and put into practice—saved my life.

That sounds dramatic.

It was dramatic. It is dramatic.

But what about the book? How did becoming a more functional adult relate to the writing of the book?

Gradually I expanded my definition of adult. I came to this, again by observations on the human body. I call it the Sign of Physical Strength and Abilities.

Oh no; you’ve got to be kidding. Haven’t we been through enough with this human body business, and signs, and self . . . What? Do you plan to write another book?

No. I don’t have to write about this because someone already did. On this occasion I had an idea, then went looking for the opinions of others to back me up. I found Rollo May’s Power and Innocence.

Rollo May says our abilities, our physical attributes and strengths give us a sense of our own power and potential, and motivate us to use those powers to change our world. This is what separates the infant from the adult—the adult finds his or her powers and uses them.

Have you known any single women in their thirties who decided to become pregnant, deliver a baby and commit themselves to raising that child, before their biological clock ran out?

Not personally. But I’ve read about it.

This drive comes right out of her body. We want to express ourselves according to our physical structure, function and strengths. Rollo May would say this is how we change the world. People can debate the appropriateness of what she does. But still, this single woman chooses to use her powers and become “mother;” the person her body tells her she is. And she changes the world by introducing one new person.

OK, so how did this relate to you?

For me, to be the adult who I am, I wanted to introduce another change in the world.

Another change?

My wife Susan and I had already influenced the world by introducing and raising four children. Also I have provided employment to a number of individuals. But still I possessed resources I had not yet put to use.

Do you mean physical resources; something in reference to your body?

No. I believe we can broaden Rollo May’s ideas to include all our resources. If I had a garage full of tools, I’d want to fix things like bicycles, cars and lawn mowers. Our resources represent our strengths. And these, whether they be physical or whatever, motivate us to put those strengths to work. Look at Matt Damon! At movie’s end his friends give him a present, a used car. So what does he do with his new resource? He takes off for the west coast to find Minnie Driver.

Oh, and that road trip illustrates something else about adults: they move out. Matt leaves Boston which earlier (while still paralyzed by his childhood trauma), he said he would never leave. The great epics illustrate this theme; the Aeneid, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. The heroes, in answer to the call on their lives—like Matt Damon—leave the security and comfort of home—and go out, and change their world.

How does “moving out” apply to you? You haven’t changed your address.

It means, figuratively speaking, getting out of my chair. It means I express my life more from doing a particular work, and less from the pursuit of material possessions, comfort and amusements. And it means pursuing that work despite the risk, the tensions and the cost.

And you have resources; you can change the world?

I can try. I can only make the effort; I cannot predict results. For resources, I have a unique background heavily influenced by death; I have a mind with a particular slant for understanding ourselves and our world; I have learned things others might find helpful; I have a computer; I know how to string words together and construct sentences; and I have hope. Hope originates in my Christian faith, and affects the way I see the world.

Tell us about hope. You mentioned it in the story. But in my opinion your references to hope come across as cryptic and vague. How does hope change the way you see the world?

Hope comes with a byproduct: realism. Go to the stories of Jesus and listen to his words. Jesus had hope. He understood that the tragedies of life do not have the final word. He saw the big picture and therefore, unlike many of us, was not intimidated by the losses and horrors of life. Instead of shying away, he could face the people and situations of his day with cold-eyed realism. For example, when he confronted the death of his friend Lazarus, he wept. He knew what death was about. He didn’t sugar-coat it with platitudes and superficial optimism. He did not rationalize it with a scientific theory in order to move the pain up into his head and thereby think it away. He allowed himself to be struck full force by the reality of death. You know, it does no one any favors when we pretend death is anything less than the horrific void it truly represents.

You learned about hope and realism from Jesus.

I also learned about it from Jacques Ellul, the French scholar. In his writings he shows how hope and realism go hand in hand. Ellul says the world needs people who can represent both: people who are rigorously honest and therefore capable of tearing down our enslaving illusions; but people who can also illustrate the pathway to life.

It sounds like the world needs therapy? Isn’t that what therapists do—they encourage you to be rigorously honest?

I agree. Robin Williams pushes Matt Damon to be honest. But I would add the world needs a certain kind of therapy. In Soul Making Alan Jones refers to shallow therapies. Not all therapies are equal. In my opinion, he put forward a therapy of substance. By integrating traditional therapy with the bigger picture—a spiritual and faith-based consideration—he lays out a path for healing which goes beyond the range of most therapies.

How does he define shallow therapies? What are those?

I don’t recall. But I know how I define it. Any therapy stopping short of resolving my conflicts over death, is too shallow for me, even if it has helped with my issues. If Ernest Becker, in his work, The Denial of Death, accurately describes the pervasive psychological and behavioral effects originating from our repressed fear of death, wouldn’t you expect us—in this most therapeutic age—to pursue a therapy addressing that psychological problem?

Summing up, I hear you saying you wrote Notes from the Flesh in order to introduce change by expressing your realistic perspective on death, and to point out an alternative.

I would state it more precisely. I wrote the book to encourage others to look at themselves and their pending death honestly, and to consider a hopeful option—the option for life.

I tell you what, we should stop here. It’s getting late and this talk has worn me out. I believe I have given you everything, the entire background story that factored into my book, Notes from the Flesh.

You haven’t told us about the people close to you, the friends who encouraged you along the way, to keep at it, to finish the story.

Well, they are a shy bunch. They prefer I not drag them out into the limelight.

OK then, let’s stop here. We covered a lot of ground this afternoon. You told us about your Growth Group and the two instrumental books affecting your group experience. We discussed the two questions influencing both the story content, and your decision to put it in writing. We even talked about two movies. You have been very generous with your time.

It’s not a problem, really.

Oh! There remains one thing you have not told us.

What one thing?

The name. What was the name of the little church in the firehouse, where your story began?

Redeemers Fellowship.